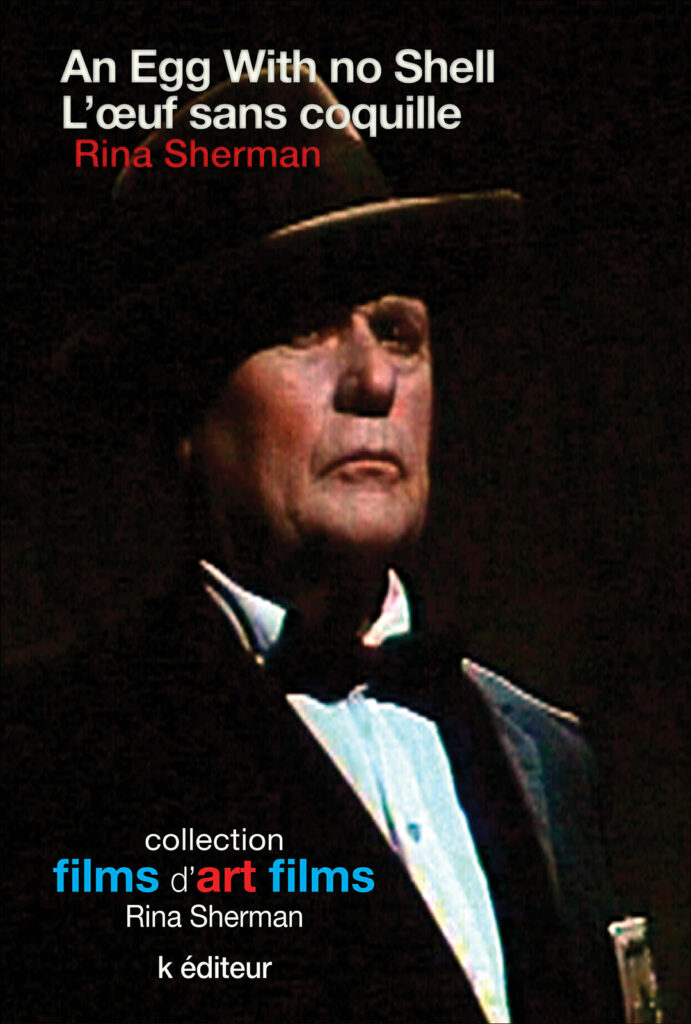

An Egg with no Shell – L’Œuf sans coquille

Rina Sherman

Un film-opéra avec Jean Rouch

Poéme urbain, films d’art films, films urbains – urban films

35 mm, couleurs, 13 min, 1992

A male diva sings in a counter-tenor voice whilst massacring chickens of all kinds brought to him by his butler, Jean Rouch. Until a slave provides proof of his love for the chicken, which he has tucked under his arm. A film-opera based on a poem, A Cock is A Woman by Rina Sherman, and a theme, Air de Paris, composed by Rina Sherman.

Un film-opéra où un homme-diva (Thierry Dubost) chante avec une voix de contralto alors qu’il massacre la poule sous toutes ses formes que lui apporte l’homme en queue de pie (Jean Rouch). Jusqu’à ce qu’un esclave vienne lui apporter la preuve de son amour pour la poule qui est blottie sous son bras…C’est alors que le cauchemar bascule dans le rêve.

Le Libretto

UN COQ EST UNE FEMME

Un poulet est une femme sans duvet.

Un poulet est une femme qui chante.

En deçà des Trois Soeurs, (2) une Zephyr (3) bleu marine s’arrête.

En deçà des Trois Soeurs, une Zephyr bleu marine

Roule de plus en plus lentement,

Quitte l’asphalte Et s’arrête à côté de tables et de chaises en béton.

Assise à côté de l’homme, une femme se penche vers l’avant

Et sort de la Zephyr,

Un rouleau de papier de toilette à la main.

Elle se dirige vers les berges d’une rivière asséchée,

Se retournant sans cesse pendant qu’elle marche.

Elle se retourne une dernière fois

Et menace du doigt son mari et son fils.

Elle porte son masque « arrête, j’aime cela ».

Elle s’incline et ses seins s’étirent loin devant elle.

Elle fait glisser son pantalon sur ses fesses,

Et ainsi accroupie, disparaît derrière une digue basse.

Un poulet est une femme sans tissu clitoridien

Et sans grandes lèvres entre lesquelles des choses peuvent être serrées.

Elle pisse sur son pantalon et sur ses jambes.

L’intérieur de ses cuisses était déjà jaunâtre

Et brûle maintenant à nouveau sous un soleil chaud.

Les poils les plus doux étaient déjà blanchis

Par toutes ces mictions salissantes.

L’homme et son fils sortent un appareil photo.

Lorsqu’elle se lève et s’incline pour enfiler son pantalon,

Ils prennent des clichés

De ses seins étirés et de ses fesses à fossettes blanches.

Elle menace alors de la tête et du doigt.

Brûlante, elle marche lentement vers l’homme et son fils.

Dans leurs yeux, elle ne voit qu’un rictus qui se rapproche.

Une Zephyr rouge roule à toute vitesse.

Sa femme regarde les Trois Soeurs par la fenêtre.

Sa fille n’est jamais descendue.

Oeufs.

2. Trois protubérances volcaniques de forme identique qui saillissent d’un paysage par ailleurs tout à fait plat.

3. Une marque de voiture.

Nota: ‘n Haan is ‘n Vrou heet eers in STET verskyn in 1982. Stet was ‘n Afrikaanse literêre tydskrif in die 1980s gepubliseer is. Die eerste uitgawe het in oktober 1982 onder die redakteurskap van Tienie du Plessis en Gerrit Olivier verskyn. Die tydskrif se naam verwys nan drukkerterm vir » laat bly ». Stet was anti-apartheid en teen sensuur. Stet het literêre en politieke kommentaar, gedigte, strokies – en fotoverhale in engels ingesluit. Die eerste uitgawe het bydraes van Olivier, Hennie Aucamp, Wilma Stockenström, Fransi Phillips, Alexander Strachan, Lochner de Kock en Dan Roodt ingesluit sowel asn onderhoud met die filosoof Johan bemoei degenaar hom.

Design affiche et photo affiche : Rina Sherman ADAGP

Interprétation

Thierry Dubost, Gammon Sharpley, Dariusz Adamsky, Jean Rouch, J.M. de La Planque, Dominique Lemeur, Christopher Archer

Thème originale

Air de Paris

Rina sherman

Musique et interprétation

Jean Pacalet

Art Directing et Costumes

Ariane Besson

Sélections festivals

Festival du Court Métrage en Plein air de Grenoble

Festival de Prades

Festival de Roanne

Festival d’ Uppsala, Suède

Weekly Mail, Johannesburg, Afrique du Sud

Festivals of Grenoble. Prades, Roanne, France. Uppsala, Sweden. Weekly Mail, Johannesburg.

L’œuf sans coquille selected for the Jean Rouch Retrospective, L’année de la France au Bresil, June 2009